Through the generosity of several kind book bloggers, readers have been finding — and responding to — excerpts from my novel, The Munich Girl.

Through the generosity of several kind book bloggers, readers have been finding — and responding to — excerpts from my novel, The Munich Girl.

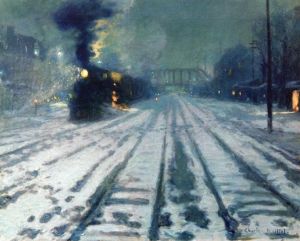

The following is from a chapter in which two lonely 16-year-olds are about to become friends when they meet on a train traveling from the Austrian border to Munich in February of 1928:

Excerpt from The Munich Girl:

As I reached for Eva’s hand, the door to the main corridor slid open and the conductor seemed to fill it with his blue uniform.

“Where did you come from?” he asked my companion accusingly.

I smelled schnapps on his breath. And saw tears gleam in Eva’s blue eyes.

“From Simbach, where she waited for this tardy train. It’s not as though she was invisible.”

His head snapped back.

“With no one there to help, she barely made it on board,” I accused.

“But I saw no one at Simbach!”

“It’s hard to see, when you’re not on the platform yourself.” Then I asked Eva, “Do you have your ticket?”

Nodding quickly, her expression like a chastened child’s, she started digging in her leather shoulder bag.

Nodding quickly, her expression like a chastened child’s, she started digging in her leather shoulder bag.

The conductor was weaving in the doorway, tapping his boot impatiently. Just like most of these useless bloody uniforms, throwing their authority around. God help you if you actually need their help. They’ll be too busy having a nip and a smoke out of sight, as this joker obviously had. Probably been drinking since we’d left Linz—he’d even neglected to announce some of the stops.

When Eva found her ticket and handed it over, he snatched it without a word, fumbling for the hole punch dangling from a chain on his waistcoat. Then he thrust it back without looking at her, muttering to me, “Your parents should have taught you better manners.”

“My parents taught me people should do their jobs, especially when jobs are scarce. And that men who want to be taken for gentlemen should behave like one.”

I took great satisfaction in saying this, though I did so in English.

Across from me, recognition sparkled in Eva’s eyes.

As he stared at me, I asked in German, “How long will it be to Munich?”

“A little over an hour,” he mumbled. When he lurched back, the door his bulky frame had propped open slid closed with a thump.

Eva burst into a shower of radiant giggles. “Now I know you are an angel.”

“As I was starting to say before we were so rudely interrupted, I’m happy to meet you, Fräulein Braun. I’m Peggy Adler.”

“Nein, nein—Eva,” she insisted. “If you don’t mind.” She used German’s familiar “du” pronoun. “I think I should be on a first-name basis with an angel, don’t you?”

“Yes, let’s dispense with formality,” I agreed, relieved. I reached into my rucksack for my Lucky Strikes. “How about a smoke? Help us relax after that ordeal?”

Eva’s eyes were like stars as she reached for one tentatively, then settled back in her seat after I lit it. Her lids fluttered shut as she took an extended drag, then exhaled with luxurious pleasure. “How wonderful. It’s been a long time since I’ve had a cigarette. And I’ve wanted one so often.”

As I inhaled deeply on my own, she said, “You speak English, and your name is English, too, yes?”

I nodded. “My real name’s Margarete, but I never use it. My father is English, and I lived there until—I came away to school in Austria.”

I’d been very close to saying, “Until my parents separated.”

“I love what you told the conductor!”

“Oh, in English, you mean? You understood?”

“Absolutely!” she replied in heavily accented English, then lapsed back into her Bavarian German. “I thought I’d choke, trying not to laugh!”

“Are you studying English at school?”

“Oh, not so very much. From films, mostly.”

“Oh, not so very much. From films, mostly.”

Now that she’d touched on one of my favorite subjects, the time and kilometers flew past as we talked about actors and music, jazz, dancing—and clothes. When I pulled out a movie magazine for us to look at, her chubby face came alive as she offered succinct assessments of the actresses’ clothes.

“I had to hide my magazines at school. Under the mattress,” she said. “My family thinks I’m going back next fall, but it’s not the life for me. I haven’t told them yet. The Sisters or my family.”

“Sounds like we’ve made the same decision. I’m not going back, either.” The thought of the scene that likely followed my unexpected departure last night launched a plummeting sensation in my stomach.

“Don’t you want to be out there in life—really live?” Eva said. “These are modern times, nicht? Not our grandmother’s days. There’s more to life than finding some lord and master and being under his thumb. I swear I’ll never live in such a prison!”

“You know,” I decided to confide as I leaned forward to light us fresh cigarettes. “My mother’s more independent now.”

“You know,” I decided to confide as I leaned forward to light us fresh cigarettes. “My mother’s more independent now.”

I stopped, suddenly. What was I doing? I never talked about the divorce.

Eva was looking at me kindly. “Oh, my parents had a time, too. When I was small.”

“My parents divorced,” I relinquished, finally. “After the war.”

Might as well get it over with. I’d probably never see her again anyway.

She reached across the gap between our seats for my hand.

Find more about The Munich Girl at: https://www.amazon.com/Munich-Girl-Novel-Legacies-Outlast/dp/0996546987

“My brother was killed, just before his nineteenth birthday. Right near the end of the war.” My voice was suddenly growing tight.

“I am so very sorry.” Eva moved to the seat beside mine and was offering a soft handkerchief.

“I tried.” I could barely get words out now. “To tell them. I knew, you see.”

I had seen it before it happened, that final end that was so horrible not only for Peter, but so many others lying there around him in that muddy, hellish mess. That place I didn’t want to see. Didn’t want to look. But it had kept coming back.

When I had tried to tell them—beg them—not to let him go, Father had called it morbid. Wicked. Been enraged that I would even suggest the danger that loomed.

Then, afterward, he’d looked at me as though I’d made that terrible thing happen to Peter, simply because I’d seen it ahead of time. And tried to warn them.